WRITING ABILITY by Nick WoodThere is an annual writing event, which I dread every year when it rolls around. It’s well known and is called NaNoWriMo and it is hash-tagged furiously on Twitter during the month of November, as people launch forth to write their novels in thirty days. Large daily word counts are flung about energetically – and, to anyone who has significant impediments to writing -- these numbers can be both intimidating and shaming. So, for the last NaNoWriMo (2020) I stayed well away, thinking about what helps each (different) writer, and why. Under the title Writing Ability, I aim to unpack: (1) some of the difficulties (and resources) of writing while disabled, as well as (2) how to write ‘authentic’ fictional characters with disabilities. And, given most stories begin with the author, I'll start there. Learning from ExperienceMy personal disabilities are now easy to name, but not so easy to live with. A clutch of incurable chronic illnesses and varied pain, which ‘significantly impairs functioning’ - to use standard disability definitions. The most active current one (Meniere’s Disease: MD) has resulted in 6 weeks plus of daily attacks of spin and vomit cycles which lasts for many hours - sometimes a full day - and lead to being pinned on a couch like a dead beetle, as any movement exacerbates the crazy spin of the world and accompanying nausea. The only medication that numbs the vestibular system in my partly deaf (inner) right ear - sufficiently for eventual relief - is a prescribed antipsychotic, which of course has its own drawbacks, i.e. ‘zombie’ brain and dry mouth. |

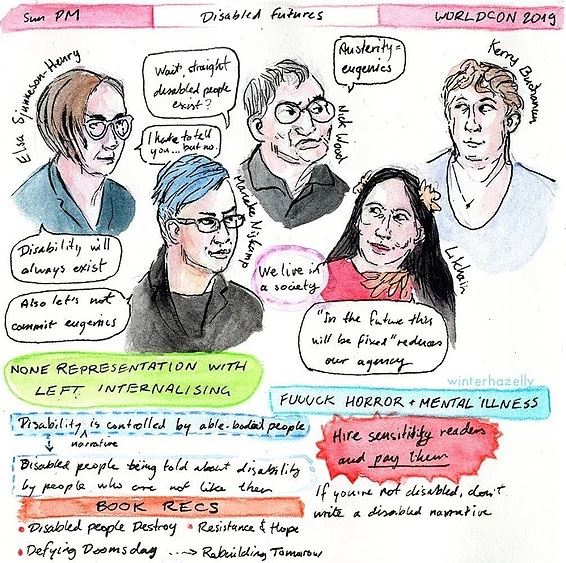

Disabled Futures by Levi Qisin |

One of the writing maxims that holds true for me is that our experiences are all grist for the writing mill. Remember, too, the more contested ‘write what you know?’ In my latest novel, Water Must Fall, I have a main character and his daughter toppling to the ground during a violent earthquake. Now, I’ve never been in a serious earthquake before, but I have made an educated guess, given this specific disability. Just last week I desperately collected meat from a chilly outside barbecue - I’m originally South African, so we can ‘braai’ in all weathers – as I felt a rapid MD attack coming on. I tottered towards the back door and, as the earth rocked and swayed from north to south, east to west, I desperately focused on trying to keep going. But thinking: The neighbours have probably always thought I’m weird cooking outside in this weather, now they must also think I’m drunk…

I found myself on my back in a thorn bush, with my supposedly loving and faithful dog trying to snaffle the sausages from the bowl that I was cradling, very protectively, on my stomach. But then help came – my partner had spotted my struggles and knew what was afoot – from this, my writing lessons learned:

(1) The hero (disabled or otherwise) can never survive adequately on his/her/their own – who helps them, and why? (2) never be ashamed to ask for help, so have characters do likewise; (3) external perceptions of an observed disability are often misleading/’ableist’/wrong and (4) loving pet dogs will keenly gnaw your bones, in a post-apocalyptic world.

Absorbing your Disabilities

I had a period of several years during my first two significant illnesses and diagnoses – between 2007 and 2009; MD and Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CP/CPPS: see the novelist Tim Parks, in Resources below) - when I wrote no fiction at all. I was too busy grappling with the traumatic experience of a pain-racked and mis-firing body, so that there was no space for imagining, only trying to get a handle on the current and unpleasantly changing reality. (I did eventually manage a published article in the British Medical Journal on ‘How (NOT) to talk to someone with an ‘Untreatable Lifelong Illness.’)

And it took me several years beyond that, before I finally accepted that I had indeed acquired (rather than been born with) a disability - and was eventually able to share this within my work context - so that ‘reasonable adjustments’ could be made under the Equality Act (2010). This included some time home working (which was nowhere near as ubiquitous, as it is now), as well as an adjustable standing desk, given I had a ‘Sitting Disability’ with CP/CPPS.

The more I learned to understand my body, the ebbs and flows of pain and impairment, the more I slowly found my way back to writing fiction. I learned not to rush – and most importantly, not to despair, through the process of finding a way to manage my new body, its’ experiences and unfolding identity.

Psychotherapy helped too, of course, given the flux and integration within/between our ‘physical’ and ‘mental’ life. Used to delivering therapy, I found out how much I now needed it, as a growing depression threatened to sabotage both sleep and my ability to face living. One dark and cold winter’s morning in 2011, I remember clearly my ‘Darkest Place’: harried by pain and despair, and finally thinking I had nothing left in me to carry on (see Resources).

I scanned the room, suddenly aware I was being watched - and saw my partner looking at me across the breakfast table, crying quietly. I knew then, that suicide was not an option. The only choice was to carry on. And so, with the help of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in particular, I began to move away from that ‘Darkest Place’ and to write it out of my system. Ten thousand words of describing pain and distress later - purely for myself - the need for recounting experiential facts ran out of steam. (I did eventually publish an account of twelve men I interviewed with the same health condition, i.e. CP/CPPS, in the British Journal of Health Psychology. Talking with others struggling to survive this, also helped me too.)

Slowly, my fiction writing started up again, and I sublimated one of my illnesses - by giving all my characters in Azania a dose of disguised Meniere’s Disease, for their act of colonising another planet. (Published in the first AfroSF anthology: All migration, voluntary or forced, carries a cost.) But what keeps you going, through the cost of illness? How can we keep writing, in the face of chronic fatigue and multiple pains and difficulties?

Pacing yourself

For me, the issues of support, pacing and self-care are key. I learned to survive through being with others who have survived before me, as we shared ways of managing our illnesses and pain – aided by finding support at home with family and, eventually, work - once I’d plucked up the courage to self-disclose.

What took me so long to disclose? I had breathed in ableist, i.e. ‘normative’ and prejudiced views about disability – such as you are ‘broken,’ ‘inferior’, or ‘malingering’ – the last word especially rang ‘true’ for me, given my pain and disability are invisible to (perhaps accordingly) sceptical others (See Ableism, in Resources). So, too, I had to learn to confront (internalised) ableist stereotypes and build a new disabled identity that gave me permission to desist being as ‘productive’ as I used to be – and to seek help to scaffold my current abilities to cope. (‘Spoon theory’ provides a visual metaphor for how many units of energy disabled people have accessible throughout the day – some days you have many spoons, most days you have few, often though, you may have none.)

And so to the issue of ‘pacing’: I write as and when I can, mostly standing, but sitting for short periods if fatigue sets in. During very disruptive active illness periods (like now) I write little and reassure myself this is fine, rather than punish myself for failing the ableist maxim ‘you should write every day!’ When feeling reasonably well, I write steadily, with frequent breaks, rather than hell for leather, like I used to – which was an attempt to get as much done before severe pain/illness disruption ensued. (I learned such ‘boom’ pressures led to ‘bust’, so better slow and steady, than fast and ‘dead’.) Most of all, I realised you end up getting more done, with a little (self) kindness.

How Best to Write Characters with Disabilities?

Let me state at the outset that in my opinion, you don’t have to be ‘disabled,’ to write characters with a disability - just as you don’t have to be black (or white) to write characters differing from your own identity (Shawl & Ward, below). But here’s an important caveat – if you are writing from outside your experience, make sure you do your homework from reputable sources to ensure your representation is sound and not imbued with harmful stereotypes. Representation matters – and, given prevalence rates of between ten and twenty percent within the overall population, if you don’t have a disabled character within a reasonably numbered set of characters, are you unwittingly erasing disabled experiences?

Some basic guidelines:

Firstly, work out why you want disabled characters in your story. Someone in a writing group I was in once, wanted to give her evil character a disability, for him to ‘stand out’. No - disability and ‘evil’ are contiguous concepts harking back to Biblical times, resurrected in the eugenics movement. This hooks directly into persisting ableist stereotypes that propagated the murder, sterilisation, and institutionalisation of millions of people with disabilities. (Only in January 2021 did University College London finally apologise for ‘its history and legacy of eugenics’, referring to racism as well as disability discrimination.)

You also need to decide whether the disability is peripheral (i.e. just part of normal human variation) or if it is central to the story – and if so, why, and how? In Allen Stroud’s gritty space opera Fearless, for example, the legless Captain Shann is not hampered by her disability in zero-g, where weight bearing is not required. In my short story "Lunar Voices (On the Solar Wind)" (winner of the Redstone Science Fiction’s Accessible Futures Contest in 2010), with the disruption of communication on the lunar surface during a solar storm, the ability to manually communicate via British Sign Language (BSL) between a deaf astronaut and the protagonist, became a life saver.

Second, why not move beyond the tokenistic and implicit ‘Rule of One’? Why should there be only one disability or disabled character? Many people with disabilities have more than one difficulty in any case – and remember a disability is not an incidental ‘tick box,’ to showcase your diversity awareness. Disability alters experiences, identities, and ways of being-in-the-world, which often chafes against an oppressive socio-political context that is riddled with ableism. (In this way there may be some corollaries with systemic racism, so Shawl and Ward’s book Writing the Other is of central use too, given its focus on intersectionality, or the multiple layering of identity.)

Third, be clear about what disability means to you and your story. Western medical definitions often essentialise disability as a medical problem operating within an encapsulated and isolated body. However, the socio-historical model of disability emphasises this is socially or medically defined, within a specific, changing, and interactive cultural and historical context, and it may be the context (not the person) that is in actuality ‘disabling.’ And science fiction worldbuilding is great for addressing changing contexts – see disability anthologies such as Defying Doomsday, Rebuilding Tomorrow and Accessing the Future. This is one of the many beauties of SF – we can think outside traditional stereotyped boxes and play with new ways of being and seeing, building ourselves and others into altered, perhaps kinder and more inclusive futures (Csicsery-Ronay, Resources).

Building Disabled Futures

The disabled activist Kenny Fries has several pertinent questions (the ‘Fries Test’) to interrogate your work for ableism:

i) Does a work have more than one disabled character? (See above)

ii) Do the disabled characters have their own narrative purpose, other than the education and profit of a non-disabled character? (A cypher to help the main protagonist progress, somewhat analogous to the ‘magical negro’ stereotype helping white characters on their ‘spiritual’ journeys.)

iii) Is the character’s disability not eradicated, either by curing or killing? The implicit assumption of ‘curing’ is that there is something ‘wrong’ that needs ‘fixing’. Elizabeth Moon’s Speed of Dark has a central character with autism faced with finding and perhaps even taking a cure for this – but will it eradicate the essence of who he is, accordingly?

And killing a disabled character, of course, carries the trauma of a eugenics history, so this needs to be very carefully considered. (See Nicola Griffith’s discussions in her #CripFic, Resources).

Own Voices

YA author Corinne Duyvis coined the term Own Voices, to articulate authors from a marginalized or under-represented group writing about their own experiences/from their own perspective, rather than someone from an outside perspective writing as a character from the underrepresented group. This attempts to centralise marginalised authors and their creations, around their own lived experiences.

This does not mean others cannot write about these experiences – but if you do, do so sensitively, with the Fries Test in mind and consult (and pay) sensitivity readers with these disabilities, wherever possible. As the disability slogan goes: Nothing about us, without us.

And Finally:

My own choice as a stand out piece of disability writing in SF, is the characterisation of Lauren Oya Olamina and her ‘Hyper-Empathy Syndrome’ in Octavia Butler’s Parable series. This syndrome is an SF construction, an invisible disability whereby Lauren literally feels the observed pain of others – and this extends to other animals too, such as a dog she is forced to shoot. She is well characterised as a ‘normal’ young teenager, albeit with a critical and organised mind that could sometimes anticipate the shape of things to come - and her disability was not aimed to ‘inspire’ anyone.

The Hyper-Empathy syndrome is viewed with prejudice - stemming from intra-uterine damage after maternal drug use - and seen by many as a weakness. So throughout her journey north, Lauren wrestles with self-disclosure, as to do so is to make herself vulnerable. But, increasingly, it also connects her with her growing band of communal travellers, disability as strength and resourcefulness too. As her developing religion, called Earthseed, affirms: "All that you touch you change, all that you change, changes you."

And that’s what my illnesses have done for me too – profoundly changed me, in positive as well as negative ways. Some of the negatives you know from above – as for the positive, I have learned to survive, and to survive with increased awareness, empathy, and kindness, for the miracle of lives and living that still surrounds and envelopes us, despite social distancing and the terrible ongoing pandemic toll (‘Dark Space’ Resources below).

I have learned greater care and kindness for my own living and the words that come from it, too. So I have given myself a big pat on the back, for being able to write this article.

Roll on, NaNoWriMo in November 2021.

To those who manage hundreds - or even thousands of words a day – I may only add fifty, but I will be happy with that.

I may write slowly, but still, I write.

Go write, with care and love.

May you have More Spoons and find Brighter Spaces.