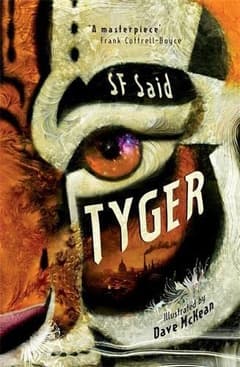

Tyger by SF Said

(David Fickling Books, 2023)

Reviewed by Kevan Manwaring

This is the fourth collaboration between SF Said and the multi-talented artist, Dave McKean (preceded by Varjak Paw, The Outlaw Varjak Paw, and Phoenix), and the integration of text and illustration is a pleasure to experience. Along with the stunning cover, endpapers, and other paratext, it is a total aesthetic experience that restores a bibliophilic delight to the reading experience. Although ostensibly in the ‘YA’ category, Tyger, like Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials and The Book of Dust, has a genuine crossover appeal that would connect with adult audiences as well as with younger readers. In a similar way to how Pullman draws upon John Milton in his series, Said here draws heavily upon William Blake—not only in the titular ‘Tyger’ of the title (an anthropomorphic and archetypal presence that looms large in the story and in the textual plane—akin to how the armoured polar bear, Iorek Byrnison does in Pullman’s universe), but in other intertextual allusions to the Lambeth-based artist and poet. The main antagonist is Urizen, Blake’s god of reason—and the Tyger is almost an embodiment of Los: his blazing deity of the imagination. Yet beneath this Manichaean conflict there are several allusions to Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience: Said draws upon the poet’s iconography (the lamb; the chimneysweep; shepherds) and cosmology. For Tyger is set in a parallel contemporary London—one of many in Said’s quantum multiverse—in which the British Empire still exists, slavery has not been abolished, and the sprawl of the city has been checked by an authoritarian, xenophobic regime. This ‘other England’ evokes the alternative London of ‘The Crystal Cabinet’, a poem featured in The Pickering Manuscript:

Another England there I saw

Another London with its Tower,

Another Thames and other hills,

And another pleasant Surrey bower.

In this other London, a secret gateway exists, connecting all the worlds. In rendering this, Said also draws upon the symbolism of another of Blake’s poems, ‘Jerusalem’:

I give you the end of a golden string;

Only wind it into a ball,

It will lead you in at Heaven’s gate,

Built in Jerusalem’s wall.

This vast cosmic drama is focalised most effectively through the viewpoint character of Adam Alhambra, a young, frustrated artist who stumbles upon the Tyger in a ruin while delivering packages for his parents’ tailoring business. Tyger revels in the ‘edgelands’ of urban spaces and foregrounds the marginalised: for both Adam and the spirited young writer, Zadie, he meets, are both from Muslim families. The real boldness and strength of Said’s novel is the way it makes such alterity not tokenistic, but central to the characters and to the plot. Tyger fearlessly addresses the topical issues of racism, inequality, and divisive manipulation of the masses. As such, there is both an ageless classic quality to the book (which certainly deserves to become one) and a painfully resonant one. There is also an ecological subtext to the story—‘tygers’ being thought extinct in the storyworld (and this world’s most endangered big cat), along with many other animals: a few token species are kept in the chief villain’s zoo—a symbol of all those trapped by the ‘mind-forg’d manacles of man’. At one point, the Tyger seems to address the reader: ‘What kind of world could kill them all? And what kind of future can such a world have?’

The story is grippingly fast paced and tense without forsaking moments of spiritual and metaphysical profundity. Said is not afraid to draw upon refreshingly anti-materialist speculations–ones that suggest a transcendental reality that is both quantum and celestial. And yet, all of this is situated within a gritty, convincingly squalid, dangerous, and dysfunctional London–one that evokes Dickens, but also modern Britain. And as in Dickens the spectre of the workhouse, of the poverty Dickens dreaded, is never far. The main arc of the plot hinges upon the emancipation of not only Adam and his family from the threat of bankruptcy, debtors’ prison, or worse, but the whole population–most of whom suffer under a never-ending burden of debt and hardship. Here, servants are acknowledged as ‘slaves’, but it is as though the whole human race of this world (and by allusion, ours) is enslaved by mental chains–and it is only through the powers of perception and imagination that true freedom can be found. In Tyger, Said and McKean has achieved this in a magnificent beast of a novel–one that has already garnered much praise. Instinctively sceptical of such hype, this reader was blown away by the sheer brilliance of this joint achievement. It is a novel that has important things to say without ever becoming didactic–it is a pure delight, reminding us of the creative possibilities and breath-taking power of words and images on the printed page.

Review from BSFA Review 20 - Download your copy here.