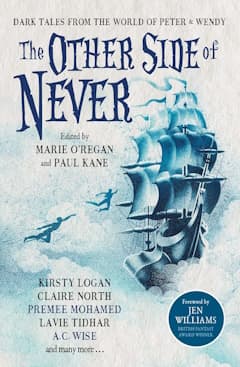

The Other Side of Never edited by Marie O’Regan and Paul Kane

(Titan Books, 2023)

Reviewed by Ksenia Shcherbino

A good story is always like an onion—it opens new layers of meaning each time you approach it. Even more so, if the book in question is Peter Pan—less than a book and more a mythology, a way of seeing the world, an identity. The protean nature of the original has its impact on its literary progeny: The Other Side of Never is a collection of short stories engaging with Peter Pan, spin-offs and palimpsests, sidequels and crossovers, re-tellings and re-imaginings, and its variety is both its strength and its weakness. I found the stories uneven in their depth, but isn’t it the essence of Peter Pan the book: as Kirsten Stirling mentions in her Peter Pan’s Shadows in the Literary Imagination (2012), the book is full of shadow-play and make belief, with various seekers searching their own truths: Peter Pan, his shadow, Wendy and Captain Hook (both with their own agenda), Wendy’s parents, their children, the crocodile, Captain Hook, the readers (and, as The Other Side of Never shows, the writers with various degrees of fascination, approval and dismissal), their own version of the boy who wouldn’t grow up.

Peter Pan is the central figure of his own myth, but it’s not just Peter Pan that stories in The Other Side of Never engage with. In “Manic Pixie Girl” by A.C. Wise we meet a self-pitying junkie (read Tinker Bell) who is keen on making better but keeps messing it up (who says that fairies can grow up?).

We have a story of Wendy in “A School for Peters” by Claire North. The title establishment is a class segregation facility in a world slightly reminiscent of The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). She doesn’t wear red, but her life is centred around looking after Peters—the elite, the imaginative, the brilliant, the rich Peters who rule the world according to their whim. As her teacher tells her, “boys cannot grow up…no matter the age of the body, boys are incapable of emotional growth and must therefore be tempered and served by girls who are more prone to aging.” Eternal boyhood is an excuse for violence and abuse, and those girls who run away are punished with beheading.

A Wendy-esque character, who is given a gift of travel between the worlds of imagination, is the protagonist of “The Land Between Her Eyelashes” by Ryo Youers. She finds out that the Neverland is healing both physically and emotionally. I loved that Youers invented a whole world for this state—the inbetweeny, one that belongs nowhere—and showed us the lighter side of escapism.

The feeling of belonging is a central focus of “A House the Size of Me” by Alison Littlewood, one of my favourite stories in the collection. In Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1911), precursor to the main body that we know now as Peter Pan, he meets Maimie who is lost in the Gardens but in the end returns back to her mother. She does not forget Peter even when she grows up, and even gives him presents, including an imaginary goat. In Littlewood’s story, however, Maimie is haunted by the Neverland. She becomes a children’s book illustrator, but when her daughter disappears, she is convinced that Peter Pan is to blame and makes a drawing of a monster that comes alive to haunt him. There is a childish malice in the act: “As a child would, Maimie has forgotten to give this thing a heart,” so the thing knows no pity.

Another Neverland-ish monster appears in the title story “The Other Side of Never” by Edward Cox. Neverland was invaded by humans after their world collapsed, and its fantasy nature banned. People live in fear of the Monster, who is rumoured to have been a beautiful boy who fell in love with a girl who grew up. Yet there is sadness in the narrator’s voice: “Never is founded on imagination, but all we could imagine was the world we’d lost,” and the only thing people could do was to bring their monsters and their fears with them.

Existential fear of fantasy, and specifically of Peter Pan, is the focus of yet another story, “Fear of the Pan-child” by Robert Shearman. It is the inbetween-ness that frightens the main protagonist, a grown-up man: “a child held fast within his own trivial fantasies and so defined by them that he would never be allowed any other life, not a jolt of it, no life, and no death.” In her essay, “Child-Hating: Peter Pan in the Context of Victorian Hatred” (2006), Karen’s Coats explored the antagonism between adulthood and childhood through the opposition between Peter Pan and Hook bordering with irrational hatred; in “Fear of the Pan-child” the fear experienced by the narrator is so overwhelming that Peter Pan is not even named—his name is blacked-out all through the story. “Fear of the Pan-child” is one of the most unusual and intertextual entries in the collection and is another one of my favourites.

Barrie’s own text is highly intertextual as it has multiple genre versions (novel, play, story that refers to other stories). Moreover, many people nowadays know Peter Pan through the lens of interpretative media (animated Disney film or live action movies, Spielberg’s Hook (1991) with a star cast of Robin Williams, Dustin Hoffman, and Maggie Smith or even this year’s Peter Pan & Wendy which I haven’t seen yet). In a similar way, The Other Side of Never brings together different ways of reading Peter Pan, you just have to find yours!

Review from BSFA Review 22 - Download your copy here.