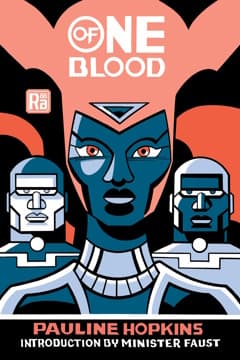

Of One Blood by Pauline Hopkins

(The MIT Press, 2022)

Reviewed by Paul Graham Raven

In reviewing this addition to MIT Press’s boldly designed Radium Age Science Fiction imprint, which is dedicated to bringing back into print seminal works of proto-sf that were originally released in the first few decades of the C20th, I find myself doing something a bit unusual: I’m going to recommend that you read Of One Blood by Pauline Hopkins even though, as a novel, it is not very good.

I generally avoid definitive statements regarding quality, and part of me would like to do so here. I am not an aficionado of the period—Of One Blood was originally published in 1902—so I cannot assess it against some accepted standard of quality, even were we able to agree on the metrics for such a measurement. Nonetheless, I can say objectively that the prose veers between overwrought and hackneyed, the pacing is erratic, and the plotting largely obvious with flashes of where-the-hell-did-that-come-from. (Apparently the story was originally written for serial publication, which goes some way to explaining its rather lurching progress: even with a solid outline to go by, a tale told in episodes can come out lumpy, particularly if there are wordcount restraints.)

So, why (re)publish such a book, or recommend it? For the avoidance of misunderstanding, I am categorically not saying that Of One Blood is not worth reading. My point is rather that Hopkins’ achievement with this novel might be hard to discern beneath the surface of a story that even the earliest and pulpiest of the short fiction magazines might have dismissed for being a bit on the crude side—or, indeed, for other reasons less ostensibly reasonable.

In his introduction to the book, Minister Faust makes a pulpit-thumping case for that achievement. Of One Blood is an ur-text of what Faust calls Afritopia: the unapologetic depiction of an imagined place and/or time in which not only is there a more advanced and utopian civilisation, but in which said civilisation is also plainly, exclusively and definitively based upon the cultural legacies of Africa and its people.

This is a double achievement, however: there’s the depiction of Afritopian futurity itself, and there’s also the significance of that representation being the early work of a Black woman journalist and author at work in the earliest years of the 1900s, which—as Faust makes very clear—was a time during which the racial-colonial logic and system imposed upon the world by white Europeans was in violent convulsion. To be the first, or among the first—for who knows how many others may have been lost to the memory-hole, deliberately or otherwise?—to write down such a vision of Blackness is an achievement in its own right; but to do so in a circumstance defined by the negation and erasure of the very idea of Black cultural heritage is even more so.

Seen from this perspective, the literary qualities of Hopkins’ book are of much lesser import; indeed, one might argue that “literary qualities” would have been among the many tools, some more subtle than others, used to prevent such a work from appearing at all. Furthermore, the book does not simply re-tread the safe themes, characters and plots of white-dominated publishing, but offers instead a vision which celebrates the long (and indeed originary) history of African culture(s), art and science—and also dares make the point, scientifically radical and controversial at that time, that Black people and the whites who still treated them as an inferior servant class (at best) were in truth, as the title has it, “of one blood”. This observation is almost banal today, to the point where it gets twisted so as to lessen or distort its import: one can all to easily imagine the “but…” which might be appended to it by some mealy-mouthed demagogue gearing up for a long hard blow on the plantation dog-whistle. When this book was originally published, though, that claim was as revolutionary as it was evolutionary—and all the more so coming from the pen (or the typewriter) of a Black woman.

Of One Blood also serves as a document of counter-hegemonic worldviews, which speak to the activities of inquiring and imaginative minds of the time. Hopkins’ story features psychic powers and seemingly magical devices—technologies (in the broadest sense of that term) of the soul which were on the frontier of psychological and medical enquiry and were informing the religions and pseudo-religions then prevalent. Hopkins’ engagement with leading currents of thought—particularly, but not exclusively, Black thought—is illuminated in Faust’s introduction: ideas which were imbricated in the foundation of the Nation of Islam in the US, and of what would become the civil rights movement, are manifest in the text.

Which is to say that Of One Blood is utopian on two levels: firstly that of its fabula, of its imagined story world, but secondly that of its context of production. The book depicts a glorious past of Blackness, and an equally glorious possible future for its Black hero-protagonist. But the historical fact of the book’s creation and publication also serves to depict the existence of a determined, resistant Black culture in a place and time in which many would assume no such thing could have existed; it is, as such, a timely rebuke to a reader like myself, who had never considered the possibility. I can only imagine that, for readers of non-white ancestry, and particularly for those of African descent, it is a powerful and inspiring precedent—not only in terms of its themes, but in terms of its very existence.

Is it a good novel? By modern standards of sf publishing, removed from its context, no; Of One Blood is not a “good” novel. But it’s a very important one—and that is why, as well as how, I suggest that you read it.

Review from BSFA Review 20 - Download your copy here.