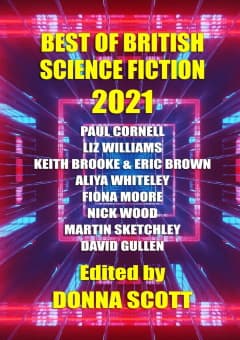

Best of British Science Fiction 2021 edited by Donna Scott

(NewCon Press, 2022)

Reviewed by Dan Hartland

The British SF of the early 2020s begs an implicit question: two decades on from the ‘British Boom’, what has been its legacy? The Boom itself is long over, its last sputterings extinguished. We should not necessarily mourn it: in the space created by the sundering of the insistent poles of Anglo-American SFF, writers of ever greater diversity have wrested the limelight for themselves—and are transforming the genre, rather than merely remixing its increasingly stale twentieth-century verities.

Has the Boom cast any shadow, then, or has it proven less influential now than it appeared destined to be at the time? On the evidence of this edition of NewCon’s annual anthology, the Boom was in some ways an aberration, not a trend. The stories collected here find comfort in forms and styles, and sometimes even settings, that would in general not have been out of place even some decades prior to the 1990s.

Take Gary Couzens’ ‘The End of All Our Exploring’—a story in which the narrator’s time-travelling paramour is assigned the mission of returning to the past to tape lost episodes of Doctor Who. Meanwhile, ‘Me Two’ by Keith Brooke and Eric Brown posits (in a not entirely considered approach to the topic) two lives lived as one: a person wakes up on alternate days first as a man and then a woman, living these lives in concert and with neither body able to meet the other—all across the course of a rather distantly experienced twentieth century (‘what use did the world of computers offer me?’ [p. 58]). In Martin Westlake’s ‘Going Home’, we spend a lot of time recapitulating the well-rehearsed events at Tunguska in 1908.

Other stories don’t hide in the past so much as set themselves in a tweedily specific present: Martin Sketchley’s ‘Bloodbirds’ lingers evocatively but to obscure purpose over the vistas of Selly Oak, and the particulars of the University of Birmingham’s red brick campus; ‘Love in the Age of Operator Errors’, by Ryan Vance, dwells damply in Edinburgh; and Tim Major’s ‘The Andraiad’, in which a deceased man is secretly replaced by his daughter with a simulacrum, is set in the mothballed confines of a parish church. These are competent stories—Majors in particular offers an atmospheric line in weirded horror, in the vein of Tales of the Unexpected—but they aren’t blazing many trails.

There are some more innovative stories here—most especially Emma Levin’s ‘A History of Food Additives in 22nd Century Britain’, which charts a century’s agricultural history with a wry, telegram-like timeline (‘The BBC begins broadcasting an emotional weather forecast […] It is agreed that emotionogenic substances must be banned’ [p. 165]). Aliya Whiteley’s ‘More Sea Creatures To See’ depicts a memorably eerie alien invasion, in which a dwindling humanity is lulled by body-snatchers impersonating the deceased (‘Our disguises will be maintained everywhere, faultlessly, until the very last one has succumbed’ [p. 197]). Elsewhere, Peter Sutton’s ‘Stone of Sorrow’ and David Gullen’s ‘Down and Out Under the Tannhauser Gate’—the first a near-future dystopia with a side-line in weird mil-sf, the other a post-invasion fantasia on a Barsoom-like Earth—both manage an elegiac mystery which approaches the transcendental.

But they can sometimes seem like islands in a sea of strange insecurity. In Liz Williams’ ‘Stealthcare’, we’re treated to an over-determined post-pandemic Britain in which the welfare state has been liquidated and everything is explicated as rapidly as possible: ‘Since the advent of stealthcare bills, as they’re not so humorously called’ we learn on the story’s first page, ‘the Brits are rueing the day that they let the old NHS slip through their fingers’ [p. 23]. This is a fine sentiment, but an alas hobbled story. Other entries, too, worry little about the elegance with which their conceit is conveyed: ‘We know that moss, lichen and algae can fuse and bond to take on new symbiotic forms,’ we are taught in Michael Crouch’s ‘The Trip’; and in the often satisfyingly spooky ‘Distribution’, Paul Cornell takes exacting care that we know exactly what to make of its villain (‘He’s the trickster, he’s everything evil in human beings. He’s Lucifer’ [p. 20]).

All of this is a shame, given the writers at work in Britain today: Nuzo Ohoh and Tade Thompson, Neon Yang and M.H. Ayinde, to name a few, are presently forging new horizons in prose of vim and vigour. In contrast, the gadgets and didacticism of this collection’s generation starships and lunar colonies—even in atmospheric stories like Philip Irving’s nicely queasy space-opera body horror ‘In Aeturnus’—can feel well-worn. For every moment of interest—in Teika Marija Smits’ often evocative ‘Girls’ Night Out’, clone-like beings bred to service human Elites enjoy a false-memoried night out—there is a reliance on exposition: ‘You never remember it afterwards […] Just in case […] you ever want to rise up against the Elites’ [p. 248]. Similarly, in ‘The Ghost of Trees’, Fiona Moore gives us—slyly, with delicious cynicism—a terraforming scientist intent on ensuring humanity fails…but her last line is a nervous summation: ‘if we can’t fix our own problems, the least we can do is make sure they don’t spread’ [p. 183].

In a 2003 edition of Science Fiction Studies devoted to the British Boom, Ken MacLeod suggested that it had found its beginning in post-Thatcher hope, an optimistic confidence. The Britain of 2021 is a great deal more exhausted and closed a place. If the Boom is to have a legacy, it must be to inspire a new radical turn. ‘We get the SF that matches our real world,’ suggested Gwyneth Jones in that same issue of SFS. The best SF also works to change it.

Review from BSFA Review 19 - Download your copy here.